Lead-In

Following the cosmic encounter in Olaf Nicolai’s Visitor, be my guest (first post in the series, step into our archive here), this next post explores two more works from the Messengers from Above exhibition that deepen the dialogue between science and art. These pieces reflect on meteorites not just as space relics, but as symbols of transformation, memory, and uncertainty. They invite us to see celestial fragments as emotional and conceptual tools, mirrors of human thought and imagination. As we move from material to meaning, the meteorite remains central: a silent messenger from the stars and a catalyst for rethinking our place in the cosmos.

Murchison, 1969, 2012 Regine Petersen (*1976), DE

Archival pigment print, 120 x 150 cm, framed

Murchison, 1969

Regine Petersen is a German visual artist whose work blends archival research with poetic visual storytelling. One of her best-known projects, Find a Fallen Star, traces the earthly landings of meteorites alongside the human stories they touch, where cosmic phenomena meet personal history. In this post, we’ll turn our gaze to another, equally compelling corner of her creative world.

In this project, Petersen places the Murchison meteorite at the center of a vast, almost immeasurable stage, one that deliberately strips away any familiar sense of scale or perspective. What the viewer encounters is an unassuming lump of material, blackened and fractured, resembling a piece of coal more than a messenger from the stars. Its outer surface, marked by a discolored fusion crust, gives no hint of the extraordinary story it carries.

This contrast is thoughtfully echoed in the exhibition catalogue, which notes: “What we see is far less than what we realize, and what we associate with what we see goes far beyond that.” It’s a fitting observation for Murchison, a meteorite that not only arrived unexpectedly but also carried within it the seeds of scientific revelation.

When scientists first examined it, they discovered something remarkable: amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, the very building blocks of DNA and RNA. In an instant, Murchison transformed from a curious rock to a scientific celebrity. It offered a rare glimpse into the chemical origins of life, propelling new ideas across disciplines and reshaping our understanding of where we come from.

Petersen’s deliberate choice to remove perspective from her visual narrative mirrors the duality of what we now know and what we still don’t. While science has uncovered some of Murchison’s secrets, much remains locked within it, echoes of potential knowledge still hidden, implications yet to be grasped. The meteorite becomes a symbol of both revelation and mystery, embodying the vast unknown still waiting in space and in ourselves.

As Paul Gauguin titled his famous work, “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?”, Murchison may offer a tentative answer to the first question. But the others remain open, their answers scattered around.

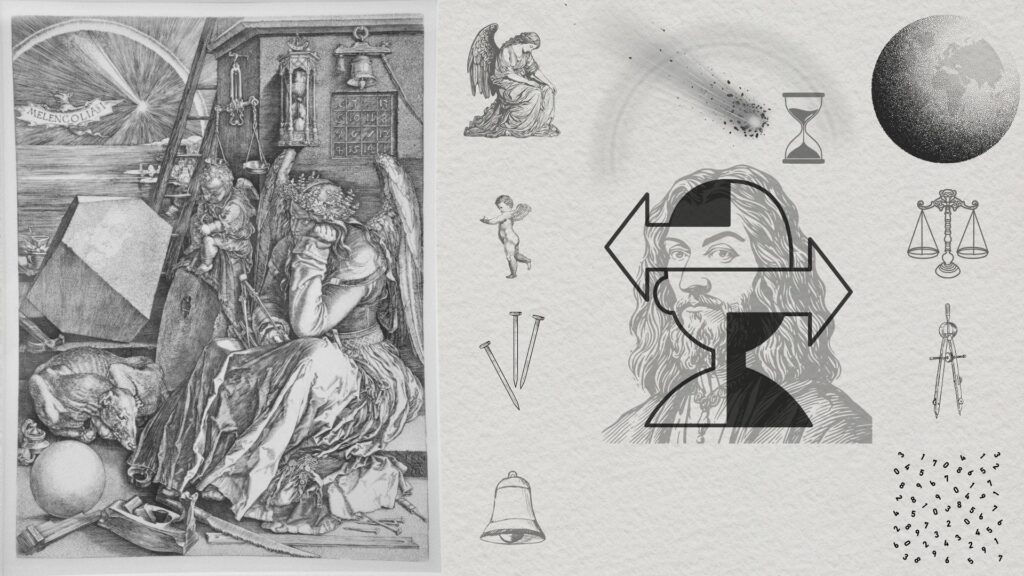

Melencolia I (Die Melancholie), 1514 Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), DE

Copper engraving on handmade paper Facsimile 24.4 x 19.1 cm, sheet, 55.5 x 42.5 cm, framed

Unfortunately for all of us, Dürer’s Melencolia I remains one of the most extensively analyzed and debated artworks in Western art history, largely because Dürer himself never offered any clues about the thoughts and feelings that gave rise to this enigmatic piece. Over the centuries, its reception by art critics, historians, and philosophers has traveled a winding path of interpretation, traversing allegorical, philosophical, psychological, and even esoteric realms.

This article, however, turns its lens toward interpretations from the 20th and 21st centuries.

20th Century Perspectives

Art critics and scholars of the 20th century, such as Erwin Panofsky, a pioneering art historian, viewed Melencolia I as a portrayal of the intellectual crisis faced by the Renaissance man, caught between the poles of faith and reason. Panofsky proposed reading Melencolia I as an allegory of melancholia imaginativa: the deep melancholy of the artist-thinker, paralyzed by the vast and often unreachable limits of human knowledge. The angel at the center of the image appears at once sorrowful and contemplative, surrounded by the scientific instruments of the era alongside symbols of spiritual faith. This internal tension, between science and belief, reason and emotion, seems to echo Dürer’s own philosophical uncertainty, and by extension, the broader epistemological crisis at the heart of the Renaissance itself.

21st Century perspective

At first glance, the engraving is a portrait of paralysis, an angel slumped in thought, surrounded by scattered tools of both faith and science. But look closer, and a deeper conflict emerges: the unresolved tension between spiritual belief and empirical knowledge. On one side, Dürer places symbols of Christian devotion, the nails and wooden planks recall Christ’s crucifixion, the ladder reaching upward a nod to spiritual ascension. The angel, divine and brooding, personifies a soul steeped in faith yet unsatisfied. Nearby, a cherubic child, perhaps a younger self or symbolic innocence, scribbles aimlessly, untouched by the turmoil. On the other side, the world of human reason lies in elegant disarray: a magic square, an hourglass, a compass, and a faceted polyhedron, each a Renaissance emblem of mathematical precision, scientific discovery, and the ambition to measure the universe. Yet none of these tools are in use; they rest idle, as if awaiting a truth they cannot reach. Caught between these two realms, the angel’s expression is not serene, it’s frustrated, restless, melancholic. And above her, streaking across the sky, Dürer includes a detail that may hold the key to it all: a blazing celestial body, likely inspired by the Ensisheim meteorite he witnessed in 1492. At the time, it defied both scriptural interpretation and scientific explanation, a real, measurable phenomenon from beyond Earth, yet utterly mysterious. For Dürer, it may have signified a rupture in certainty, a glimpse of something greater that neither faith nor science could yet claim. And so the angel waits, trapped in the chiaroscuro between belief and reason, longing for a sign that never quite arrives. Melencolia I is not just a portrait of melancholy, it is a meditation on the limits of knowing, etched at the threshold of the modern age.

In the context of Messengers from Above, the meteorite arrival scene “is highly dramatic and effectively counteracts the rigid inactivity of the personification of Melancholy, who is caught up in her doubts” (Messengers from Above. Meteorites – Mysterious Objects from Outer Space, 5 December 2024 – 27 September 2025, ERES Stiftung, München).

The meteorite’s dramatic arrival disrupts the stasis, serving as a symbolic counterweight to the angel’s inertia. It introduces a surge of potential energy into the composition, a reminder that even when the mind is paralyzed by doubt, the cosmos continues in motion. Yet this motion remains ambiguous, its trajectory uncertain and elusive. Far from offering clarity, it denies resolution, offering only the unsettling awareness of forces beyond comprehension. Rather than alleviating the angel’s despair, this cosmic intrusion deepens it, confronting the artist, and, by extension, humanity, with a world in which meaning is no longer given but must be forged in isolation, without guarantees.

Contemporary art criticism sees Dürer’s Melencolia I as a richly layered symbol of the creative mind’s struggle with knowledge, doubt, and the limits of human existence. It is a profound meditation on the paradox of creativity, both a source of power and a cause of existential melancholy, making it a timeless masterpiece whose relevance persists into the 21st century.

Links

Messengers From Above exhibition at the ERES Foundation.

Exhibition catalogue available at the ERES Foundation.