Lead-In

Having lingered with some of the most remarkable specimens in the Messengers from Above exhibition (third post in the series, step into our archive here), we arrive now at a final reflection, a small but telling measure of the shifting vantage point that recent years have brought to the study of meteoritics.

Besides the very important fact of being an emerging field of study, micrometeoritics pushes us to acknowledge the underlying bias in one’s ontological and self-identity awareness. Our minds are brilliant biological machines, and they are amazing at seeing things belonging to discrete categories with fixed essences, and less keen to give space to the overlapping or relational. This is why Western society tends to pursue an analytic cognitive style, at the expense of a holistic one. Thus, no human would ever think that they interact with “outer space,” which might be a fair first conclusion.

However, science suggests that we should expect one extraterrestrial particle with a diameter of 0.1 mm per square meter per year. So, if you haven’t cleaned the gutter of your balcony in the past years, just be aware that “outer space” is not necessarily starting beyond the Kármán line (~100 km altitude); rather, it starts with the dust that we are so eager to keep out of our homes. In fact, out there is in here.

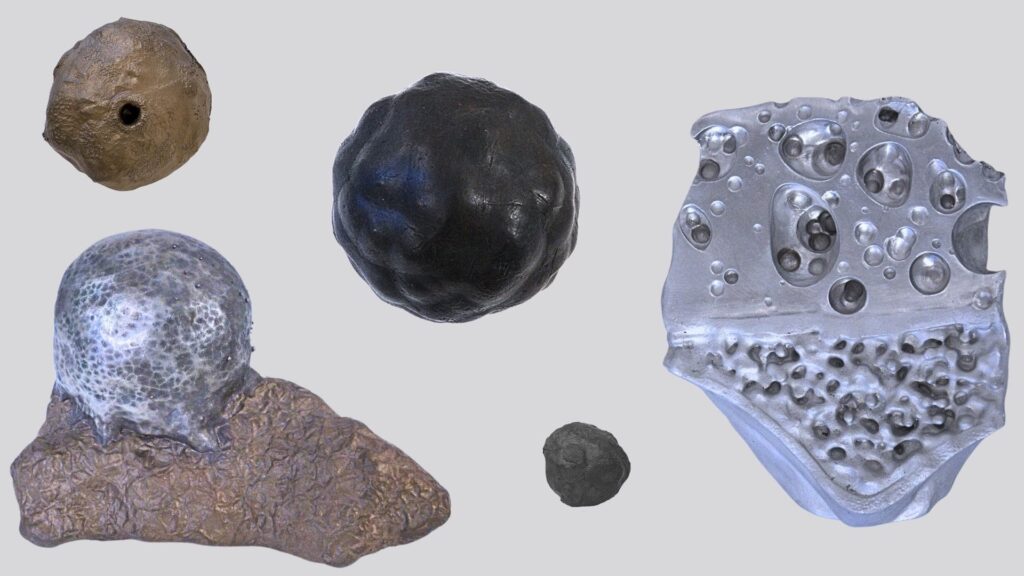

Micrometeorites found on Earth are cosmic spherules that have survived entry through Earth’s atmosphere. They are shaped as a spherule, a solidified melt droplet of stone and/or metal, due to how surface tension warps the liquid rock into a sphere during the high-velocity pass through the atmosphere. They come in roughly three flavors: unmelted, partially melted, and fully melted.

The biggest challenge that we face in the process of finding micrometeorites is how to distinguish them from all the anthropogenic sub-millimeter particles.

Dust Buddies, 2023 / 2024 Sonia Leimer (*1977), IT

Installation, 7 Objects Bronze, aluminum, and mixed techniques

Sonia Leimer is a Vienna-based artist with many works that incorporate space as a major theme. The artist’s vision of space is not bound to a defined and bordered understanding. Leimer rather likes to move between spaces, from real to imaginary, and yet hold them all simultaneously, leaving the viewer to feel and probe the nature of these simultaneously coexisting worlds. Above all, her work mandates a reflection on the consequences arising from the intersection of these different realms of space.

“Dust Buddies“ by Sonia Leimer, as seen through MeteoriteMixology’s eyepiece.

Leimer’s “Dust Buddies” artistic piece’s conceptual foundation lies within the recent importance given by scientific research to the “stardust” from which the solar system came to form. In her case, stardust has valence I in the notion of micrometeorites, whereas the Earth-bound dust is of valence II. With the support of the Natural History Museum Vienna, Leimer frantically examines under the microscope material collected by herself from various rooftops. The analysis reveals a plethora of unexpected structures from the micro-space of common dust.

“Dust Buddies” is nothing more, nor less, than the upscaling of the structures that hide in the dusty micro-space, which, even though part of our physical world, our imagination tends to neglect or even forget due to the great distance imposed by sheer scale. Differences in scale render shapes different in these worlds, and they can only be grasped via imagination.

The skillfully crafted bronze or aluminum structures reveal both extraterrestrial material and human-made industrial residues dating back to the start of the Industrial Revolution, captured with the precision and intimacy of a single palm of dust collected from any rooftop. Thus, Leimer’s dust sculptures unite the human and cosmic dimensions. The artwork is locked in the sense that none of the dust particles divulge any affiliative affinity toward the worldly or the extraterrestrial realms. It’s up to the viewer’s imagination!

Such man-made particles contaminate everything, no matter how remote the location. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, the since-formed geological strata are already impregnated with many kinds of wird anthropogenic structures.

It is then important to stare into the eyes of the following dilemma: how the primordial material from micrometeorites, the one that made up the solar system right from the beginning, is now lost among similar copies, made by a species that originates from that very primordial material.

Links

Messengers From Above exhibition at the ERES Foundation.

Exhibition catalogue available at the ERES Foundation.