Meteorite Ilustrations - Falling Stones, Rising Perspectives

At MeteoriteMixology, we surely love a good story!

However, we do not want to analyze our way too deep into anything. Through these drawings, we just want to resurface the general human perspective state when these depictions surfaced for the first time. To hint towards how these “signals” became the defining aspects of those times, and how people gathered to form the wave that shaped those shores.

This post wants to reemerge the drawings, to stir your quiet craft of perception, and then later… maybe hint you to assess what it is that can, or should (in case you feel strongly about it), be noticed through the perspective of today. Notice the signals that rise, any slight movement that might take contour in whatever corner, be it a smooth or wrinkled surface that is a woven part of you.

When looking at these drawings, it is important to keep in mind that they were made by individuals who picked up the “signal” of their times, and pursued something that made them feel true to themselves, something that made them feel true to the greater humanity that existed in their contemporaneity.

When looking at the drawings, notice if these aspects reflect back differently to you than they did to them.

Disclaimer: The meteorite specimen representations shown below are original, but they have been removed from their original backgrounds and gathered into composite figures. The backgrounds used in these figures have been slightly modified in hue compared to the originals. In the source materials, each specimen was presented separately.

Middle Ages: The gospel of “50/50, either divine blessing or apocalyptic end”

The Middle Ages are characterized by extreme hardship and a very short human lifespan, death being everywhere. No wonder that human perception and beliefs were populated with religious symbolism that tended to belong in two big general categories:

Good omens: divine love, help, reward, blessings, health, luck.

Bad omens: death in many forms (sickness, war, starvation, execution).

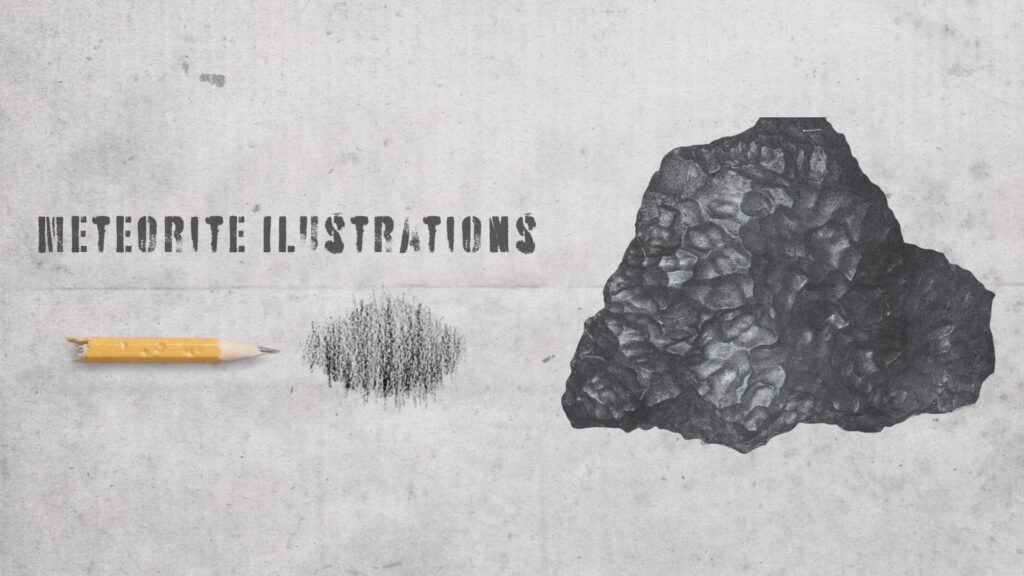

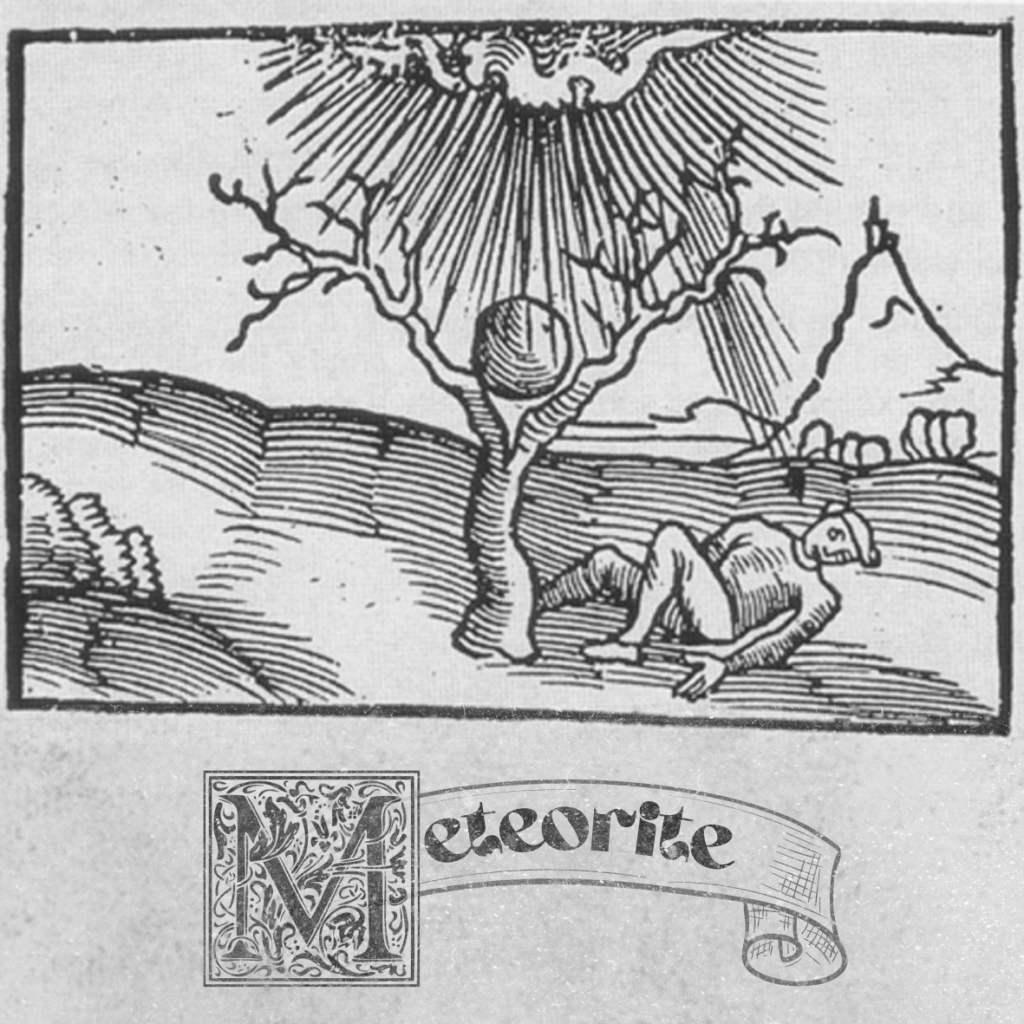

Long before the notion of falling stones from the heavens found its scientific footing, people spoke of “thunderstones,” charms or omens tossed down by inscrutable forces. What passed for illustration in those times was rarely an attempt to capture the object itself; instead, symbols and signs sufficed, as though the stones belonged more to the invisible order of alchemy and cosmology than to the physical world. Their images drifted free of scale or substance, flat silhouettes, decorative borders, and gentle gestures of ink that revealed more about belief than about the stones’ true nature.

Artists were not striving for empirical truth but for allegory. They adorned these celestial curiosities with flourishes, trusting intuition and tradition over observation. Texture was suggested rather than studied, mass was imagined rather than measured. It was an age in which drawing served as a vessel for meaning, not a tool for inquiry, and the hand that drew was guided more by inherited stories than by the patient scrutiny of the eye.

“Establishing reality” - The turning point of Enlightenment

Some of those who felt inspired by such strange rocks felt that humanity was asking way too much from such unanimated objects, and that most probably very intriguing stories, but of a different kind, were at play. It must have felt easier to just step back, stay aware, and notice whatever the world had at play. This approach of noticing and then analyzing was the kick-start for one of the greatest discoveries: that meteorites fall from the sky, and they are extraterrestrial. Visual documentation of any fall becomes the ultimate proof.

This era is marked by a strong desire to gain a steady hand on pencil by the scientists of the time. They are simply not willing to give space to trained artists yet; they are still stuck in the position of the Vitruvian man, that can do it all, the multifaceted, the skilled, the erudite homo sapiens in sciences and art. Thus, they prefer to learn, train, and gain the necessary drawing skills.

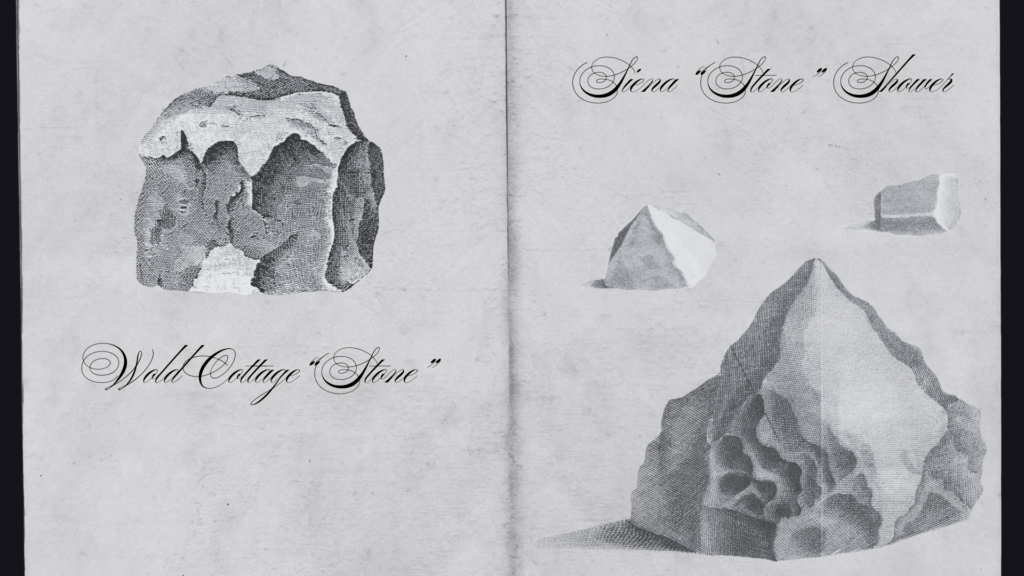

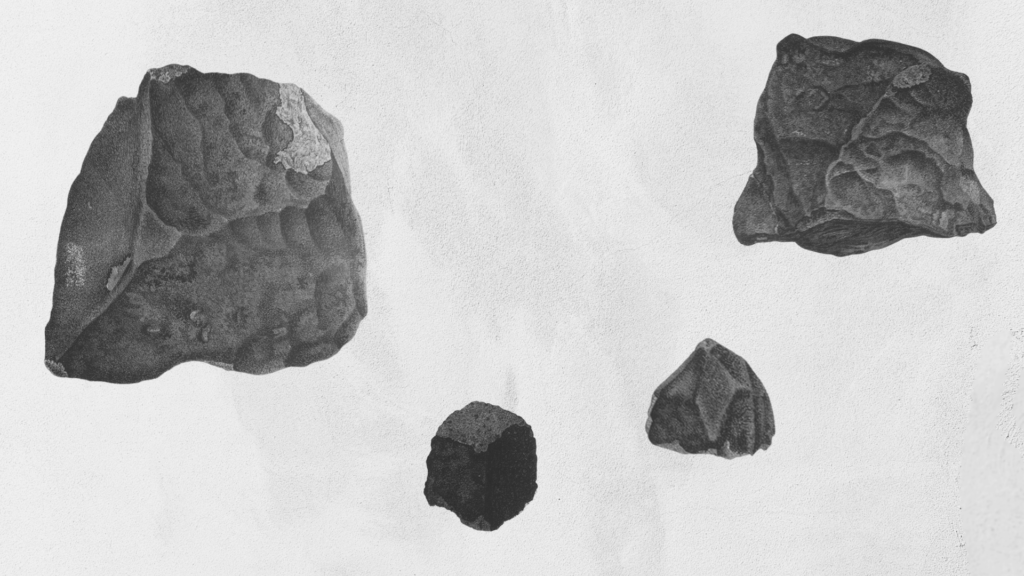

Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni best adopts an empirical realism in his meticulous work, achieving rational compositions with balanced framing at realistic scales. He emphasizes structure and surface texture. Through shading (cross-hatching), he manages to give the depicted specimens weight proportional to their real size and provides the necessary fidelity to enable comparative studies on different specimens from various fall sites.

From Object to Specimen, from 1840 to 1870

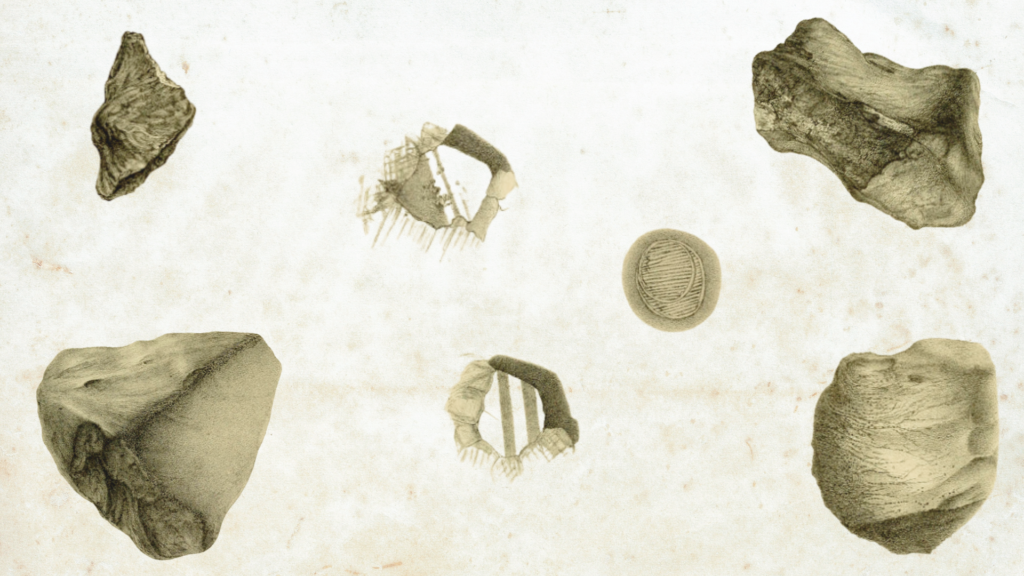

Now that “meteorites are falling rocks from space” had sunk in as the fundament of meteoritics, every stone turned into a valuable specimen for mineralogic and crystallographic study.

In order to come up with a classification method, to establish the so much needed order in the realm of meteoritics, scientists needed to study in detail all the physically accessible characteristics of the available samples. But sample sharing was difficult and cumbersome, so the best option was to make high-fidelity drawings that could be disseminated easily between scientific institutes.

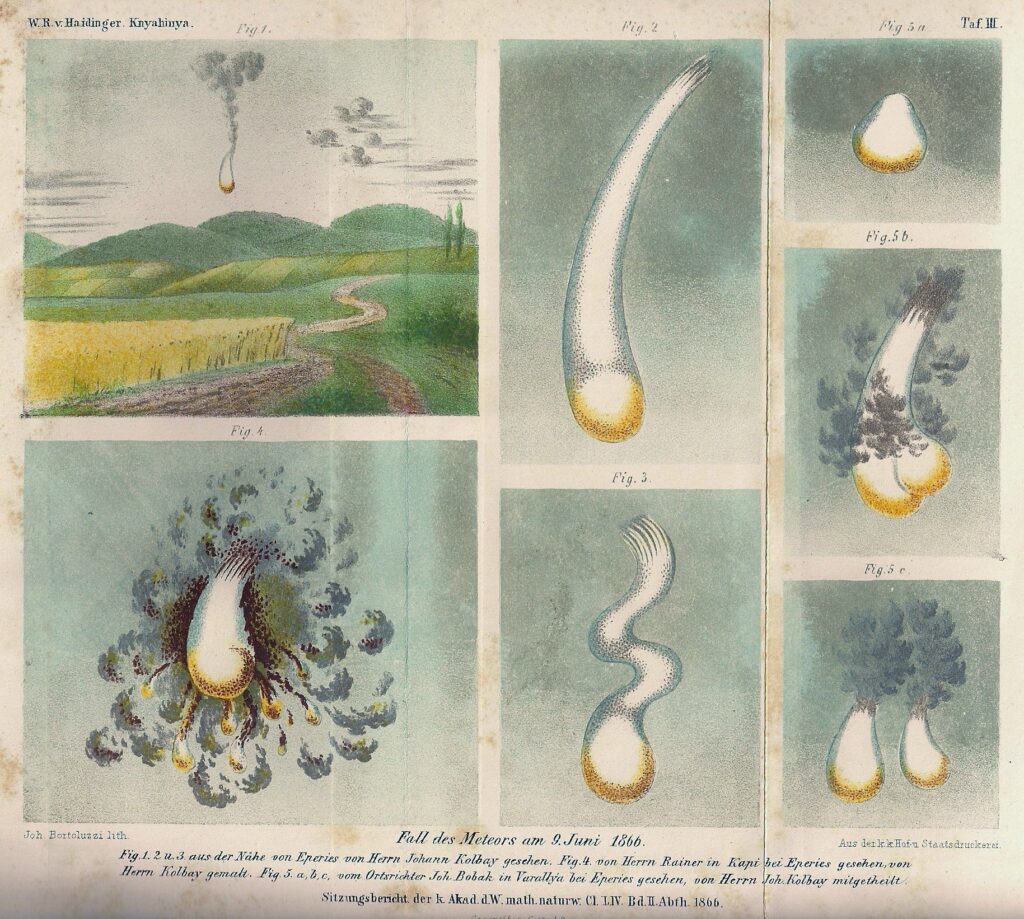

This was the time when many artists were hired to create plates that resembled fine-art still lifes, which had to be precise yet also aesthetically well composed. Scientific realism is employed in the form of tonal lithography, where focus is placed on materiality (metallic sheen, texture). This period turns out to be the one when highly skilled artists were trained in mineralogy and crystallography, with the utmost purpose of balancing scientific realism with the soft, yet deep touch of art. They ended up mastering the visual translation of microscopic or polished sections onto paper. Moreover, they pushed the boundary of detail representation, making flight orientation analysis possible down to the lowest level of visually noticeable crust flow lines. Thin sections and mineral grain depictions form the double-edged sword that cuts through the borders of knowledge and manifestation of art.

In the 19th century, observers of meteorite falls often concentrated on analyzing the stones themselves. At the same time, many aspects of the meteorites’ arrival, such as the speed, trajectory, and fragmentation, remained ambiguous. Capturing these fleeting details required not only careful attention but also a well trained eye and hand.

During meteorite falls, only trained observers tended to record such fine details: the brightness and colors of the fireball, the trajectory and length of the smoke trail, the duration and persistence of the glow, and any fragmentation of the main mass. Such meticulous observations were made, for example, during the Knyahinya fall of 1866.

Visual Evidence and Hybrid Media, from 1870 to 1910

By the turn of the century, all the large institutes that held the biggest collections managed to put together meteorite catalogues that quickly became indispensable for any reputable scientist. This was an achievement that came on the horseback of technological advancement in chemistry, but most importantly optics and photography. These are the times when drawings start to slowly be replaced with skillfully made photographs, deemed to be the ultimate way of showing an object in an unbiased and objectively neutral state. We have to give them a bit of credit, because little did they think about aspects such as the ones captured in the following quote “Photography is an art of observation. I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.”, back in those days.

This was a moment in which drawn figures sat beside early photographs, each medium trying to assert its authority. Optical microscopy and polarizing lenses opened the meteorite to a world of hidden structures, revealing colors, cleavage lines, and crystalline habits that had previously lived in secrecy. Photography, still young and imperfect, stepped onto the stage as both ally and challenger. Its presence forced the draftsman to reconsider his role, yet it never fully replaced the human hand; instead, the two worked side by side, each compensating for the other’s limitations.

*Collotype plates are an early photographic printing method, invented in the 19th century, used to reproduce images with high detail and continuous tones (shades of gray) rather than just black-and-white dots.

20th & 21st Century Changes

Throughout the 20th century, chemistry, especially its applied and instrumental branches, advanced rapidly, and meteorite research shifted accordingly. Instead of focusing primarily on visually striking specimens, scientists increasingly relied on diagrams, elemental ratios, isotopic measurements, and laboratory analyses to interpret meteorites. The dramatic, almost artistic aspect of meteorite study gradually receded. Yet the stories uncovered through these scientific diagrams more than compensated for that loss, revealing deep insights into the origin of the solar system and, ultimately, the origin of ourselves.

With the advent of the digital era, meteorites have become more accessible than ever. Many specimens can now be explored as 3D digital models, examined through spectral analyses, or even virtually “touched” in VR environments. Add to this the flood of high-definition images from space missions and sample-return probes, and it becomes clear that we are living in an extraordinary moment. The field has grown wild, rich, and full of enthusiasm like never before. More on these exciting developments will come in future posts.

The End

References

[1] – Marvin, Ursula B. “Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni (1756–1827) and the Origins of Modern Meteorite Research.” Meteoritics & Planetary Science 42, no. 9 (Supplement) (2007): B3–B68. http://meteoritics.org

[1.1] – Sixteenth-century sketches of fallen stones: an explosion in the sky expels a spherical ceraunia that splits a tree while a small triangular glossoptera is about to strike a man already prone from the blast (Reich, 1517; courtesy of Prof. Owen Gingerich, Harvard University).

[1.2] – Engraving of the Wold Cottage stone made for Captain Topham’s handbill; the stone measured about 70 cm in its longest dimension (Gentlemen’s Magazine, July 1797, Item No. 4 from Figure 1).

[1.3] – “Stones fallen from the stormy cloud on the 16th of June, 1794”: Individual engravings showing the Siena meteorite shower, including the largest stone A (5 pounds) and smaller stones B–E. Endplate from Soldani (1794), courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

[1.4] – von Schreibers. Supplement to Chladni’s Book (1819), Plate II. 1820. Engravings of stones from the Eichstädt, Tabor, Siena, and L’Aigle meteorite falls.

[2] – Tschermak, Gustav. “Über die Meteoriten von Mocs (Mit 2 Tafeln).” Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften 85 (1882): 195–209.

[3] – Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Knyahinya Meteorite Fall [Image]. In Wikipedia. Retrieved November 23, 2025, from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Knyahinya_Meteorite_Fall.jpg

Author and source details: Haidinger, W. R. von. “Knyahinya Meteorite Fall.” Sitzungsberichte der mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Jahrgang 1866. Public domain (copyright expired).

[4] – Döll, Eduard. “Zwei neue Kriterien für die Orientirung der Meteoriten (Mit vier Lichtdrucktafeln, Nr. VI–IX).” Jahrbuch der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt 37 (1887/1888): 193–206.